Last year, a friend asked if I wanted to meet the man known as AM Radio. I never expected to meet him.

If the world of MMOs has a Banksy, it's AM Radio. But where the

British street artist is famous for his sardonic graffiti mysteriously

appearing around the globe, AM Radio is famous for creating artwork in Second Life, the user-created virtual world packed full with rich experiences.

Even years after the height of his renown, AM Radio is probably Second Life's most famous artist. The New York Times Magazine featured his Second Life work, as many other outlets have. But more than that, his work drew a passionate following in the game itself. Players often see works by grassroots creators on popular platforms that allow user-generated content, like Minecraft and Skyrim — and that brings the creators a measure of fleeting internet fame.

AM Radio's acclaim, however, was in another category altogether. Some of his most avid admirers told him that his work saved them from suicide. Two people who met as avatars in the middle of his most famous art installation wound up getting married in real life. Women constantly followed AM Radio around Second Life the way you imagine ladies from another time trailing after a Parisian painter — sometimes they even propositioned him sexually with real nude photos of themselves. Now, five years past the apex of his fame, he still attracts thousands of visitors with every single Second Life installation — 12,000 in the last year.

And then, in 2011, something else happened to heighten his allure. AM Radio suddenly disappeared from Second Life. And so did his creations — all but one.

The mystery of his disappearance lingered for a couple years. Since I'd written about his Second Life art many times for a metaverse blog, I had his email address. I sent him several messages. I received no reply.

AM Radio's fame came despite the fact that the wider Second Life user community didn't know his real identity. It left his fans with no easy way to find him. More key, he'd made it plain many times that he wanted to keep his real and virtual identities apart.

Two years later, a mutual friend met him at South by Southwest, and knowing I was there too, encouraged him to reach out. This e-mail appeared in my inbox: "AM Radio here. I tweeted in your direction, but it was only my second tweet ever, and I don't know if it went through... Would love to meet you in person, even if you're busy, a moment or two would be fun."

So I went to meet AM Radio, and the man who made him real.

Even years after the height of his renown, AM Radio is probably Second Life's most famous artist. The New York Times Magazine featured his Second Life work, as many other outlets have. But more than that, his work drew a passionate following in the game itself. Players often see works by grassroots creators on popular platforms that allow user-generated content, like Minecraft and Skyrim — and that brings the creators a measure of fleeting internet fame.

AM Radio's acclaim, however, was in another category altogether. Some of his most avid admirers told him that his work saved them from suicide. Two people who met as avatars in the middle of his most famous art installation wound up getting married in real life. Women constantly followed AM Radio around Second Life the way you imagine ladies from another time trailing after a Parisian painter — sometimes they even propositioned him sexually with real nude photos of themselves. Now, five years past the apex of his fame, he still attracts thousands of visitors with every single Second Life installation — 12,000 in the last year.

And then, in 2011, something else happened to heighten his allure. AM Radio suddenly disappeared from Second Life. And so did his creations — all but one.

The mystery of his disappearance lingered for a couple years. Since I'd written about his Second Life art many times for a metaverse blog, I had his email address. I sent him several messages. I received no reply.

AM Radio's fame came despite the fact that the wider Second Life user community didn't know his real identity. It left his fans with no easy way to find him. More key, he'd made it plain many times that he wanted to keep his real and virtual identities apart.

Two years later, a mutual friend met him at South by Southwest, and knowing I was there too, encouraged him to reach out. This e-mail appeared in my inbox: "AM Radio here. I tweeted in your direction, but it was only my second tweet ever, and I don't know if it went through... Would love to meet you in person, even if you're busy, a moment or two would be fun."

So I went to meet AM Radio, and the man who made him real.

A second glance at Second Life

Buzzed by media reports between 2006 and 2008 as the internet's next big thing and then largely forgotten afterward, Second Life is actually a bit more popular now than it was during that time — it had about 500,000 regular users then, and now it has around 600,000.

After the excessive media coverage waned, and the initial hyperbolic

predictions failed to cash out, many forgot about it, but more kept

playing.

Created by a San Francisco startup called Linden Lab, Second Life was inspired in great part by the Metaverse in Neal Stephenson's Snow Crash — a 3-D alternate reality with its own rules, values, and hierarchies. Like Minecraft, Second Life also comes with construction and scripting tools so users can create 3-D content in the virtual world with multi-shaped building blocks, then animate them with interactive scripts.

Launched in 2003, Second Life combined the Metaverse aspiration with those proto-Minecraft aspects and bolted them atop social MMO game mechanics, like user-to-user ratings, friending, leaderboards, and so on. In its first five years, the creative energy that gamers put into Second Life was fierce and unpredictable. For its first three years, Linden Lab contracted me as the virtual world's official "embedded journalist" — it was a lot like trying to report on a collective hallucination. One of the very first users I interviewed, a tall brunette dressed like a prototypical hacker, had built a glass-domed mansion in Second Life. In real life, she was homeless. Someone who used to work for Peter Molyneux built an island with its own ecosystem. Someone else created a four-dimensional tesseract house with no front or back.

The outside media began noticing the virtual world. In 2005, MTV showed up at Second Life's first user convention. In 2006, Businessweek put Second Life on its cover, because by then, businesses earning millions from creating and managing content in Second Life were emerging. (Linden Lab allows users to buy and sell Second Life's virtual land and exchange the in-world currency, the Linden Dollar, for real money.) More media appearances followed: A cameo on The Office; a segment on The Daily Show. Major companies began investing to have a Second Life presence: IBM, Reuters, CBS, Dell, Armani, American Apparel and countless more. But most Second Life activity (then and now) actually happens in its diverse sub-communities of users: fashionistas with their own magazines, runway models, participants in catty social dramas, roleplayers acting out endless narratives in vampire castles or Gorean empires or post-apocalyptic wastelands and sexual subcultures, some with kinks so strange and violent they’d shock even the most jaded liberal.

At the height of Second Life's hype wave, the world resembled a libertarian fever dream with garish sci-fi cities and fantasy sex palaces strewn right alongside official corporate headquarters and high-toned shopping malls, and everywhere above you, it seemed, were blinking billboards. (Not to mention intermittent storms of giant, flying dildos.) It was crass, endlessly chaotic and mostly ugly.

And then amid all that, often by accident or via word of a friend, players come across a work by AM Radio. And the light itself seems to change — the outside cacophony is forgotten.

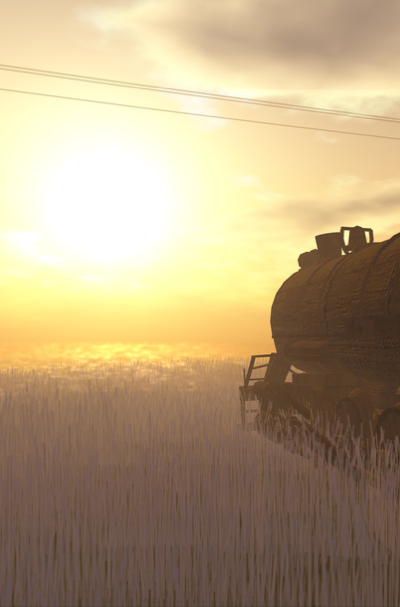

The first work in Second Life to bear AM Radio's name was "The Far Away," a Midwestern wheat field players could walk around in, often making them feel wistful for a time and place they likely never knew. It felt like being immersed in Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven, like walking through a golden expanse near a rusty train with tracks seemingly lost beneath the windblown grain and a magic hour sky.

Second Life players, learning about the place, would teleport or fly there in an endless stream of avatars whose incongruous appearance made these settings seem even more surreal — sex vampires and robot furries and supermodels and space commandos and cyberpunk cowboys all milling about in God’s country. In an anonymous interview, AM Radio suggested he was creating these rustic places to puncture the virtual, to offer a glimpse of the real:

"Sunlight, for our generation, is something seen through Plexiglass windows, and my art is a reaction against that ... an attempt to tear down the fakery, all that plastic in impossible colors and awful rugs and terrible media, like television ... And now, here I am in a virtual world, trying to create the organic."

And AM Radio kept building. He made "The Quiet," a sad and desolate cabin surrounded by magic and wind, bereft amid drifts of silent snow. He recreated Jacques-Louis David's "Death of Marat" as a 3-D interactive experience, so any avatar could be the one to die like Marat. He built a strip of highway with a red doorway that opened into dreams. He made a place called "Superdyne," which was an infinite desert expanse with a sewing machine and a long sheet of blue fabric held aloft, caught in a windstorm that lasted forever. These settings often include old radios and transistor tubes or ancient cars and planes, or they're pierced by unexpected, mystic elements. They were 3-D sculptures that were mostly not animated, but their textures had a vivid lucidity that made them seem vibrant and alive. AM Radio made all this and much more. And as each new creation appeared in Second Life, word of mouth spread and thousands of avatars endlessly teleported there for weeks, months, years after.

And sometimes, if players were lucky, they'd also meet AM Radio himself, an avatar as evocative as his creations: a tall man with a scarf and top hat, a quiver of sticks at his back and a sensitive, wistful face. Often he’d stand there and amicably chat with the people who came to see his works. He didn't publicly share much about his life beyond the virtual world, except the broadest details — he was American, he worked for a major corporation. I met him many times in Second Life — usually, a coterie of admirers (mostly women) was there as well, attentive to his every chat message.

AM Radio was not the only artist in Second Life; others have also experimented with the virtual world as a medium. French filmmaker Chris Marker (creator of the classic La Jetée), created Second Life machinima. Acclaimed Chinese conceptual artist Cao Fei sold an entire virtual city in Second Life to a collector for $100,000. Then there were the virtual artists creating, not for a pre-existing audience in galleries and museums, but for the community of Second Life players who’d attend openings of new installations with the kind of avidness you see at a SoHo premiere. Among them: Bryn Oh, creator of fragile steampunk scenes, like "Stay with me"; Gryph Glaves, who wired a Kinect Up to Second Life, so he could literally turn his face into a dynamic sculpture poking its way into the virtual world; Cutea Benelli and Blotto Epsilon, who built an eerily strange, self-assembling, self-destructing city. These artists, for a time, even had a leading patron and maven — an elegant woman named Beverly Millson, a longtime lover of virtual reality who spent her days handling PR for a bionics startup, then worked nights and weekends promoting a community of artists through her avatar, sometimes greeting her admirers in a ballgown made from a school of fish.

In retrospect, the virtual world was in too much havoc for AM Radio’s sudden departure to register. In the summer of 2010, a year after AM Radio’s admiring profile in the New York Times, Linden Lab laid off a third of its staff. With the media hype long over, the world was not adding users, so existing members felt the pain. In October of that year, in an apparent bid to shore up its revenue further, Linden Lab ended its discount on virtual land owned by non-profit and educational organizations. Tumult ensued: Countless educators pulled up stakes. Harvard and Princeton owned virtual islands in Second Life, as did hundreds of other organizations. Amid the user outrage at Linden Lab, relatively few seemed to notice AM Radio's quiet announcement that his installations, which were being hosted on Ball State University's Second Life island, would also leave when the island underneath it went away. Amid this bitter unraveling, even Beverly Millson grew disenchanted about the future of virtual world art.

But Beverly hadn't forgotten about AM Radio. And after finding him, she asked me if I wanted to meet him too.

Created by a San Francisco startup called Linden Lab, Second Life was inspired in great part by the Metaverse in Neal Stephenson's Snow Crash — a 3-D alternate reality with its own rules, values, and hierarchies. Like Minecraft, Second Life also comes with construction and scripting tools so users can create 3-D content in the virtual world with multi-shaped building blocks, then animate them with interactive scripts.

Launched in 2003, Second Life combined the Metaverse aspiration with those proto-Minecraft aspects and bolted them atop social MMO game mechanics, like user-to-user ratings, friending, leaderboards, and so on. In its first five years, the creative energy that gamers put into Second Life was fierce and unpredictable. For its first three years, Linden Lab contracted me as the virtual world's official "embedded journalist" — it was a lot like trying to report on a collective hallucination. One of the very first users I interviewed, a tall brunette dressed like a prototypical hacker, had built a glass-domed mansion in Second Life. In real life, she was homeless. Someone who used to work for Peter Molyneux built an island with its own ecosystem. Someone else created a four-dimensional tesseract house with no front or back.

The outside media began noticing the virtual world. In 2005, MTV showed up at Second Life's first user convention. In 2006, Businessweek put Second Life on its cover, because by then, businesses earning millions from creating and managing content in Second Life were emerging. (Linden Lab allows users to buy and sell Second Life's virtual land and exchange the in-world currency, the Linden Dollar, for real money.) More media appearances followed: A cameo on The Office; a segment on The Daily Show. Major companies began investing to have a Second Life presence: IBM, Reuters, CBS, Dell, Armani, American Apparel and countless more. But most Second Life activity (then and now) actually happens in its diverse sub-communities of users: fashionistas with their own magazines, runway models, participants in catty social dramas, roleplayers acting out endless narratives in vampire castles or Gorean empires or post-apocalyptic wastelands and sexual subcultures, some with kinks so strange and violent they’d shock even the most jaded liberal.

At the height of Second Life's hype wave, the world resembled a libertarian fever dream with garish sci-fi cities and fantasy sex palaces strewn right alongside official corporate headquarters and high-toned shopping malls, and everywhere above you, it seemed, were blinking billboards. (Not to mention intermittent storms of giant, flying dildos.) It was crass, endlessly chaotic and mostly ugly.

And then amid all that, often by accident or via word of a friend, players come across a work by AM Radio. And the light itself seems to change — the outside cacophony is forgotten.

The first work in Second Life to bear AM Radio's name was "The Far Away," a Midwestern wheat field players could walk around in, often making them feel wistful for a time and place they likely never knew. It felt like being immersed in Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven, like walking through a golden expanse near a rusty train with tracks seemingly lost beneath the windblown grain and a magic hour sky.

Second Life players, learning about the place, would teleport or fly there in an endless stream of avatars whose incongruous appearance made these settings seem even more surreal — sex vampires and robot furries and supermodels and space commandos and cyberpunk cowboys all milling about in God’s country. In an anonymous interview, AM Radio suggested he was creating these rustic places to puncture the virtual, to offer a glimpse of the real:

"Sunlight, for our generation, is something seen through Plexiglass windows, and my art is a reaction against that ... an attempt to tear down the fakery, all that plastic in impossible colors and awful rugs and terrible media, like television ... And now, here I am in a virtual world, trying to create the organic."

And AM Radio kept building. He made "The Quiet," a sad and desolate cabin surrounded by magic and wind, bereft amid drifts of silent snow. He recreated Jacques-Louis David's "Death of Marat" as a 3-D interactive experience, so any avatar could be the one to die like Marat. He built a strip of highway with a red doorway that opened into dreams. He made a place called "Superdyne," which was an infinite desert expanse with a sewing machine and a long sheet of blue fabric held aloft, caught in a windstorm that lasted forever. These settings often include old radios and transistor tubes or ancient cars and planes, or they're pierced by unexpected, mystic elements. They were 3-D sculptures that were mostly not animated, but their textures had a vivid lucidity that made them seem vibrant and alive. AM Radio made all this and much more. And as each new creation appeared in Second Life, word of mouth spread and thousands of avatars endlessly teleported there for weeks, months, years after.

And sometimes, if players were lucky, they'd also meet AM Radio himself, an avatar as evocative as his creations: a tall man with a scarf and top hat, a quiver of sticks at his back and a sensitive, wistful face. Often he’d stand there and amicably chat with the people who came to see his works. He didn't publicly share much about his life beyond the virtual world, except the broadest details — he was American, he worked for a major corporation. I met him many times in Second Life — usually, a coterie of admirers (mostly women) was there as well, attentive to his every chat message.

AM Radio was not the only artist in Second Life; others have also experimented with the virtual world as a medium. French filmmaker Chris Marker (creator of the classic La Jetée), created Second Life machinima. Acclaimed Chinese conceptual artist Cao Fei sold an entire virtual city in Second Life to a collector for $100,000. Then there were the virtual artists creating, not for a pre-existing audience in galleries and museums, but for the community of Second Life players who’d attend openings of new installations with the kind of avidness you see at a SoHo premiere. Among them: Bryn Oh, creator of fragile steampunk scenes, like "Stay with me"; Gryph Glaves, who wired a Kinect Up to Second Life, so he could literally turn his face into a dynamic sculpture poking its way into the virtual world; Cutea Benelli and Blotto Epsilon, who built an eerily strange, self-assembling, self-destructing city. These artists, for a time, even had a leading patron and maven — an elegant woman named Beverly Millson, a longtime lover of virtual reality who spent her days handling PR for a bionics startup, then worked nights and weekends promoting a community of artists through her avatar, sometimes greeting her admirers in a ballgown made from a school of fish.

In retrospect, the virtual world was in too much havoc for AM Radio’s sudden departure to register. In the summer of 2010, a year after AM Radio’s admiring profile in the New York Times, Linden Lab laid off a third of its staff. With the media hype long over, the world was not adding users, so existing members felt the pain. In October of that year, in an apparent bid to shore up its revenue further, Linden Lab ended its discount on virtual land owned by non-profit and educational organizations. Tumult ensued: Countless educators pulled up stakes. Harvard and Princeton owned virtual islands in Second Life, as did hundreds of other organizations. Amid the user outrage at Linden Lab, relatively few seemed to notice AM Radio's quiet announcement that his installations, which were being hosted on Ball State University's Second Life island, would also leave when the island underneath it went away. Amid this bitter unraveling, even Beverly Millson grew disenchanted about the future of virtual world art.

But Beverly hadn't forgotten about AM Radio. And after finding him, she asked me if I wanted to meet him too.

At the height of Second Life's hype wave, the world resembled a libertarian fever dream.

Lifting radio silence

AM Radio is a man in his 30s named Jeff Berg; he is tall, bearded,

broad-shouldered, with long, blonde hair and rangy, hippie handsomeness

some would later compare to Shannon Hoon, the late frontman of Blind

Melon. Berg was in Austin for South by Southwest in 2013 on behalf of

his company, so we met at a hotel courtyard overlooking Congress Avenue

Bridge, from which, during dusk, hordes of bats emerge.

We sat at an outdoor table facing that bridge, and Berg spoke with a quiet calm. He told me that Beverly and I were among the very few Second Life players to meet him in person, in real life. One of the very first Second Life players he met was by accident: Berg was getting coffee at his local shop and happened to overhear the two attractive girls behind the counter talking about Second Life. As she prepared his order, one barista enthused about a beautiful wheat field she had just visited there. And Berg realized she was talking about "The Far Away."

And so, Berg says, "I grabbed my coffee and thanked them and ran out the door."

The bashfulness he describes belies the serene confidence Berg has now. And as he told me about his history as AM Radio — beginning then in Austin, then continuing intermittently over the successive months — I began to understand why.

We sat at an outdoor table facing that bridge, and Berg spoke with a quiet calm. He told me that Beverly and I were among the very few Second Life players to meet him in person, in real life. One of the very first Second Life players he met was by accident: Berg was getting coffee at his local shop and happened to overhear the two attractive girls behind the counter talking about Second Life. As she prepared his order, one barista enthused about a beautiful wheat field she had just visited there. And Berg realized she was talking about "The Far Away."

And so, Berg says, "I grabbed my coffee and thanked them and ran out the door."

The bashfulness he describes belies the serene confidence Berg has now. And as he told me about his history as AM Radio — beginning then in Austin, then continuing intermittently over the successive months — I began to understand why.

"I grabbed my coffee and thanked them and ran out the door."

From serendipity to Second Life

When you see AM Radio's avatar with his top hat with goggles,

greatcoat and cane, you might picture a life of quirky adventure. As it

turns out, Jeff Berg has a bit of that too: After graduating from an

East Coast art college, he went to Ireland on a whim, wandering the

green countryside as a drifting artist, supporting himself with drawings he sold to passers-by.

Along the way, he met an Irish girl who planned to study in the

American Midwest, and he followed her there. They broke up, so he worked

in a bookstore for a while, and eventually, wound up with a job offer

at one of the world's largest tech companies as a graphics artist and

interface designer. His boss suggested he explore a thing called Second Life, which everyone was talking about at the time.

So AM Radio was born. "It was always serendipitous," he says. Or, as he adds: "Oops, Second Life."

And when he created in Second Life, that was serendipitous too. Someone told him it was impossible to build a field of wheat in the game, so he built one. And that wheat field became famous — it was one of the first revelations that someone could evoke powerful emotions within a virtual, shared 3-D space.

Berg created his AM Radio avatar to be long-limbed and gentle, and it took him quite a while to realize why he had created him that way. It actually took his therapist, whom he told about Second Life, to point out that the avatar looked liked Berg's father as a young man. A lot of Berg's family history makes its way into his Second Life creations. In younger years, his father sold radio parts and transistors, elements which show up throughout Berg’s art. The snowfield he'd come to build in Second Life was inspired by his grandfather. Among the last interactions with the old man before he died was in winter, when they stood together to measure the height of the outside snow. So while he sought to create something organic and real in a virtual world, Berg was also virtually recreating memories of his family — and through his own avatar, his childhood memories of his father.

So for Berg, "The Far Away," like the rest of his Second Life art, "was a framework for my own memories," drawn from earlier times as a boy living in the American countryside.

But after he had built "The Far Away," a strange thing started happening.

Players from Poland and Canada and even China started coming up to him, convinced those fields were based on those from their own countrysides. "Have you been there?" they asked him. "It looks exactly the same." People would see in his Second Life work things that weren't even there: "If you actually zoom in on the wheat," Berg says now, "I drew that with my own hand." Consequently, his wheat didn't really wave in the wind — but people swore to him that it did. "And I knew something exciting was possible."

And as Berg's Second Life art gained fans and growing interest, so did his Second Life avatar. Often they didn't just admire his 3-D work, but spoke of a deeper bond.

"I would run into people [in Second Life] who told me, 'I get your work, so you must get me.' So people would be very open to me," Berg remembers. Often these admirers were keenly depressed people, and they would send him instant messages while he was at work. Feeling a sense of obligation, he made a point of replying to these IMs as soon as he got home. At least once, the message was from someone who was simultaneously so depressed and so moved by Berg's Second Life work, the person announced to Berg that they were about to commit suicide. "And I had to talk them down."

Many of AM Radio’s fans were women, and many desired the man behind the avatar. One took topless photos of herself, and sent them to his Second Life inventory.

"I tried very hard to be friends," he says now, "and not take anything beyond that." He did so because he's committed to someone in real life. "And also at the same time ... I didn't want them to walk away with their interactions with my artwork and feel like it was a terrible experience."

So AM Radio was born. "It was always serendipitous," he says. Or, as he adds: "Oops, Second Life."

And when he created in Second Life, that was serendipitous too. Someone told him it was impossible to build a field of wheat in the game, so he built one. And that wheat field became famous — it was one of the first revelations that someone could evoke powerful emotions within a virtual, shared 3-D space.

Berg created his AM Radio avatar to be long-limbed and gentle, and it took him quite a while to realize why he had created him that way. It actually took his therapist, whom he told about Second Life, to point out that the avatar looked liked Berg's father as a young man. A lot of Berg's family history makes its way into his Second Life creations. In younger years, his father sold radio parts and transistors, elements which show up throughout Berg’s art. The snowfield he'd come to build in Second Life was inspired by his grandfather. Among the last interactions with the old man before he died was in winter, when they stood together to measure the height of the outside snow. So while he sought to create something organic and real in a virtual world, Berg was also virtually recreating memories of his family — and through his own avatar, his childhood memories of his father.

So for Berg, "The Far Away," like the rest of his Second Life art, "was a framework for my own memories," drawn from earlier times as a boy living in the American countryside.

But after he had built "The Far Away," a strange thing started happening.

Players from Poland and Canada and even China started coming up to him, convinced those fields were based on those from their own countrysides. "Have you been there?" they asked him. "It looks exactly the same." People would see in his Second Life work things that weren't even there: "If you actually zoom in on the wheat," Berg says now, "I drew that with my own hand." Consequently, his wheat didn't really wave in the wind — but people swore to him that it did. "And I knew something exciting was possible."

And as Berg's Second Life art gained fans and growing interest, so did his Second Life avatar. Often they didn't just admire his 3-D work, but spoke of a deeper bond.

"I would run into people [in Second Life] who told me, 'I get your work, so you must get me.' So people would be very open to me," Berg remembers. Often these admirers were keenly depressed people, and they would send him instant messages while he was at work. Feeling a sense of obligation, he made a point of replying to these IMs as soon as he got home. At least once, the message was from someone who was simultaneously so depressed and so moved by Berg's Second Life work, the person announced to Berg that they were about to commit suicide. "And I had to talk them down."

Many of AM Radio’s fans were women, and many desired the man behind the avatar. One took topless photos of herself, and sent them to his Second Life inventory.

"I tried very hard to be friends," he says now, "and not take anything beyond that." He did so because he's committed to someone in real life. "And also at the same time ... I didn't want them to walk away with their interactions with my artwork and feel like it was a terrible experience."

"I would run into people [in Second Life] who told me, 'I get your work, so you must get me.'"

From Second Life to self esteem

As Jeff Berg became famous in Second Life as AM Radio, and as his work changed people’s lives, their response to him began to change Berg himself. Before Second Life, he had low self-esteem at work, and resisted advancement opportunities for that very reason. But now that people in Second Life

were clamoring to meet AM Radio in-world, and because he felt obliged

to meet them, he also found it easier to engage with people he met in

the real world and assert himself more. At his company, he tells me, he

became more outgoing, more willing to take on leadership roles. Before

becoming a famous avatar, that would have been impossible.

"Being AM Radio absolutely got me past a barrier," he says, "because I had to." Self-esteem and confidence thrived, and even three years later, remains: "I will talk with anyone," he says. "I cannot be a fly on the wall."

So while Berg's work as AM Radio is behind him, the person I meet in Austin still reflects the changes his avatar has bestowed on him — no longer a bashful artist fleeing from baristas, but someone more outgoing and contained. Indeed, as we talk, spectacularly attractive women in cowboy boots and skintight jeans, there for SXSW, keep giving Berg sidelong looks as they pass, perusing his long hair and self-assured air, likely wondering what rock star he must surely be. And while they do, Berg tells about the end of his Second Life career.

As AM Radio's fame grew, the balance between that fame and the demands of Berg’s real life began to fray. "I was literally neglecting the people around me," Berg says. Not just family, but those in his career. "As soon as I felt it was impinging on work, I said, 'You know what, this doesn't feel right.'" On top of that, he felt he was starting to neglect his work as a photographer and painter.

And so with that, AM Radio largely faded away.

And because they were being hosted on the virtual land of a university closing down its Second Life presence, nearly all of AM Radio’s Second Life creations disappeared from the world too.

"When that went, all my locations went," says Berg. "I got offers from others [to host them] but the terms and timing never worked out." They once existed in physical (virtual) form, but because he has no backup copies, they are fully gone. Ironically, Linden Lab still uses the screen shot of an AM Radio installation on the 404 error page of the Second Life website.

For those who joined Second Life after 2011, this may be their first and only encounter with AM Radio’s creations.

Second Life patron and AM Radio admirer Ziki Questi stepped in at the last moment to take ownership of "The Far Away," Berg’s last remaining AM Radio installation in Second Life, which is also the first he built in 2007. (If you have the game's viewer installation, you can log in and visit it directly here.) Seven years after its creation, Questi says, dozen of users still visit every day.

"Being AM Radio absolutely got me past a barrier," he says, "because I had to." Self-esteem and confidence thrived, and even three years later, remains: "I will talk with anyone," he says. "I cannot be a fly on the wall."

So while Berg's work as AM Radio is behind him, the person I meet in Austin still reflects the changes his avatar has bestowed on him — no longer a bashful artist fleeing from baristas, but someone more outgoing and contained. Indeed, as we talk, spectacularly attractive women in cowboy boots and skintight jeans, there for SXSW, keep giving Berg sidelong looks as they pass, perusing his long hair and self-assured air, likely wondering what rock star he must surely be. And while they do, Berg tells about the end of his Second Life career.

As AM Radio's fame grew, the balance between that fame and the demands of Berg’s real life began to fray. "I was literally neglecting the people around me," Berg says. Not just family, but those in his career. "As soon as I felt it was impinging on work, I said, 'You know what, this doesn't feel right.'" On top of that, he felt he was starting to neglect his work as a photographer and painter.

And so with that, AM Radio largely faded away.

And because they were being hosted on the virtual land of a university closing down its Second Life presence, nearly all of AM Radio’s Second Life creations disappeared from the world too.

"When that went, all my locations went," says Berg. "I got offers from others [to host them] but the terms and timing never worked out." They once existed in physical (virtual) form, but because he has no backup copies, they are fully gone. Ironically, Linden Lab still uses the screen shot of an AM Radio installation on the 404 error page of the Second Life website.

For those who joined Second Life after 2011, this may be their first and only encounter with AM Radio’s creations.

Second Life patron and AM Radio admirer Ziki Questi stepped in at the last moment to take ownership of "The Far Away," Berg’s last remaining AM Radio installation in Second Life, which is also the first he built in 2007. (If you have the game's viewer installation, you can log in and visit it directly here.) Seven years after its creation, Questi says, dozen of users still visit every day.

"Being AM Radio absolutely got me past a barrier, because I had to."

A third life for Jeff Berg

Last year, Jeff Berg logged into Second Life after many

months of absence. He was trying to find a new connection with the

world, a source of inspiration, but he couldn't. Something else held him

off.

"I think what's not bringing me back, was a little bit of fear ... fear of all those obligations coming back, and taking over my life again." But even as he remains disconnected, Second Life keeps calling him back. He still gets messages from time to time from people who miss him — that is to say, who miss AM Radio.

"From an emotional level," says Berg, "you have to be OK about people cutting you off and feeling like you abandoned them."

But Berg remembers his work there and the people who admired it with affection. "A few months of showing your artwork in Second Life can be like a lifetime of feedback and art critiques," he says. Thousands of screenshots and machinima videos of his Second Life work still exist on social media, finding new admirers. And while his installations are gone from the virtual world, he evinces little regret at their digital dematerialization: "I ask back at you, what installations? Perhaps," Berg says, "I merely recognized when a good snowfall could happen in a virtual world, and that the ephemeral nature of it was integral."

Berg has gone back to painting and photography, with a vision renewed by his virtual world foray. Now with the real-world confidence he gained from being AM Radio, he's also succeeded as a leader in his company, even heading the team that created a civic data system that won a Webby award last year. Berg was at the ceremony to accept it.

"I was up on the same stage as Jerry Seinfeld and Kevin Spacey and also got made fun of by Patton Oswalt in front of a thousand people, which was actually a lot of fun." (Oswalt was the Webby's emcee, and as Berg turned to leave the stage, he notes, Oswalt "said something like, 'I didn't know Shannon Hoon was still alive!' which got a good laugh from the audience.")

None of this is to say that Berg's given up on Second Life. "I think any technology platform has a chance to regain any of its old glory," he says. He cites Apple here, reminding me of its pre-iPhone era, when Steve Jobs' company floundered as a quaint niche.

"We could read about [Second Life's return] next week," Berg says. He thinks someone could tomorrow create a new experience in the game that's so immersive and emotional, people would want to go back and experience it again and again.

To his point, Linden Lab recently launched a beta version of Second Life integrated with the Oculus Rift. The company also just announced development of an entirely new virtual world, which will reportedly have a VR component. The founding creators of Second Life have also moved on in a Rift-ward direction: Philip Rosedale is now building High Fidelity, a next-generation virtual world integrated with the Oculus Rift. Rosedale's first CTO, Cory Ondrejka, now a VP at Facebook, sat right next to Mark Zuckerberg when final negotiations of the social network’s purchase of the VR company were made. In a very direct sense, virtual reality now is in many ways a continuation of what Linden Lab and users like Berg pioneered in the old days.

"Oculus Rift keeps returning to my radar," Berg says. "I hope to be in a position to try it out someday, or perhaps ... create something for it." Many other artists will do so as well, and like Berg did before them, they may find themselves overwhelmed by their virtual fame and the passion it inspires. If they are lucky, they will, like Berg, find themselves challenged to become better versions of themselves in the real world too.

Asked if he has any advice for the new generation of virtual artists, Berg had this to share: "[W]elcome new mediums, but don't let yourself be guided by them... Wyeth's paintings were never about watercolor, or wheat fields. It was about the expression and the way of seeing the world, and using a dry brush technique that conveyed the quiet, thoughtful mind behind it. Calvin and Hobbes surely wasn't about the newspapers' color print process capable of printing those beautiful half page spreads, but was about Bill Watterson's understanding of the medium, audience, and himself." And therefore, this: "Avoid showcasing a particular technological capability," Berg says, "but instead, build experiences that remind us how human we are and have always been."

"I think what's not bringing me back, was a little bit of fear ... fear of all those obligations coming back, and taking over my life again." But even as he remains disconnected, Second Life keeps calling him back. He still gets messages from time to time from people who miss him — that is to say, who miss AM Radio.

"From an emotional level," says Berg, "you have to be OK about people cutting you off and feeling like you abandoned them."

But Berg remembers his work there and the people who admired it with affection. "A few months of showing your artwork in Second Life can be like a lifetime of feedback and art critiques," he says. Thousands of screenshots and machinima videos of his Second Life work still exist on social media, finding new admirers. And while his installations are gone from the virtual world, he evinces little regret at their digital dematerialization: "I ask back at you, what installations? Perhaps," Berg says, "I merely recognized when a good snowfall could happen in a virtual world, and that the ephemeral nature of it was integral."

Berg has gone back to painting and photography, with a vision renewed by his virtual world foray. Now with the real-world confidence he gained from being AM Radio, he's also succeeded as a leader in his company, even heading the team that created a civic data system that won a Webby award last year. Berg was at the ceremony to accept it.

"I was up on the same stage as Jerry Seinfeld and Kevin Spacey and also got made fun of by Patton Oswalt in front of a thousand people, which was actually a lot of fun." (Oswalt was the Webby's emcee, and as Berg turned to leave the stage, he notes, Oswalt "said something like, 'I didn't know Shannon Hoon was still alive!' which got a good laugh from the audience.")

None of this is to say that Berg's given up on Second Life. "I think any technology platform has a chance to regain any of its old glory," he says. He cites Apple here, reminding me of its pre-iPhone era, when Steve Jobs' company floundered as a quaint niche.

"We could read about [Second Life's return] next week," Berg says. He thinks someone could tomorrow create a new experience in the game that's so immersive and emotional, people would want to go back and experience it again and again.

To his point, Linden Lab recently launched a beta version of Second Life integrated with the Oculus Rift. The company also just announced development of an entirely new virtual world, which will reportedly have a VR component. The founding creators of Second Life have also moved on in a Rift-ward direction: Philip Rosedale is now building High Fidelity, a next-generation virtual world integrated with the Oculus Rift. Rosedale's first CTO, Cory Ondrejka, now a VP at Facebook, sat right next to Mark Zuckerberg when final negotiations of the social network’s purchase of the VR company were made. In a very direct sense, virtual reality now is in many ways a continuation of what Linden Lab and users like Berg pioneered in the old days.

"Oculus Rift keeps returning to my radar," Berg says. "I hope to be in a position to try it out someday, or perhaps ... create something for it." Many other artists will do so as well, and like Berg did before them, they may find themselves overwhelmed by their virtual fame and the passion it inspires. If they are lucky, they will, like Berg, find themselves challenged to become better versions of themselves in the real world too.

Asked if he has any advice for the new generation of virtual artists, Berg had this to share: "[W]elcome new mediums, but don't let yourself be guided by them... Wyeth's paintings were never about watercolor, or wheat fields. It was about the expression and the way of seeing the world, and using a dry brush technique that conveyed the quiet, thoughtful mind behind it. Calvin and Hobbes surely wasn't about the newspapers' color print process capable of printing those beautiful half page spreads, but was about Bill Watterson's understanding of the medium, audience, and himself." And therefore, this: "Avoid showcasing a particular technological capability," Berg says, "but instead, build experiences that remind us how human we are and have always been."

Images: Jeff Berg, Ziki Questi

No comments:

Post a Comment